Feminism, Urbanism, And Transit Advocacy

Considering women's needs while advocating for a sustainable future.

Recently, I published a post which detailed how “environmental” activism, such as urbanism and transit advocacy, should also take social justice into consideration. I wanted to write a standalone post on how urbanists and transit advocates should consider feminism when fighting for solutions.

After all, the ways in which we interact with each other also dictate how we interact with the world around us.

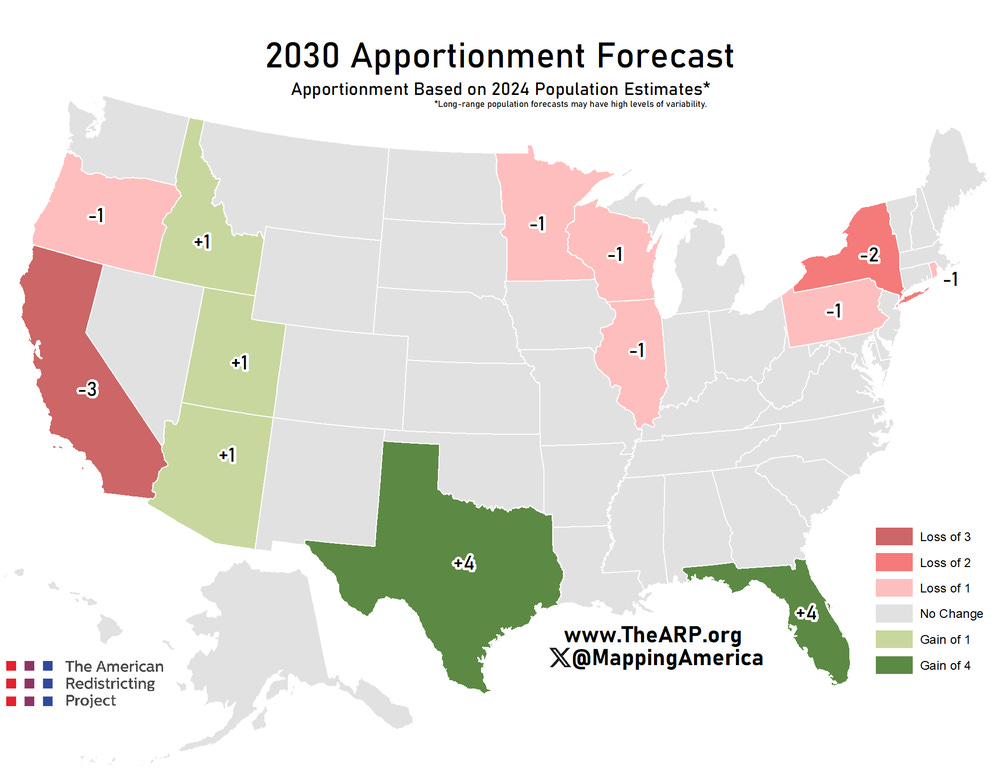

In my opinion, urban activism will be the next major movement to sweep across the United States. The single-family home, once the centerpiece of the American Dream, is unaffordable across much of the country. Our housing crisis is contributing to a mass exodus from blue states to generally cheaper red states, and this population shift will play a role in the 2030 redistricting and re-allocation of electoral college votes.

The obvious solution to this problem is to build more housing to meet demand, but many places are constrained by space. Take Silicon Valley, home to the most expensive housing markets and rental prices in the country. As the name suggests, it’s a valley, and the entire area is already one massive suburb, so there’s not a lot of room left to expand. Except, that is, for up.

The traditional single-family home will face a reckoning, as cities must become more dense to create supply that will lead to lower rent prices.

As they do this, cities will need to address how they approach transportation. As density increases, it will be more convenient to have amenities such as grocery stores and cafes located in leased units on the ground floor of an apartment complex. People won’t have to drive as far to run errands, get to work, or drop their kids off at school.

Ideally, they would not need to drive at all. Cities will need to prioritize much more sustainable modes of transportation. This includes walking and biking for short trips, and buses and trains for longer ones. This is not to say that the car will entirely disappear, but our currently car-centric cities will need to be radically changed, shifting away from private transportation.

While the urbanists and transit advocates of tomorrow are fighting to make change in their local areas, they need to take civil rights into account, too. How can they balance the needs of different groups of people to make change as equitable as possible?

This is where feminism comes into the picture. It’s imperative that urbanists and transit advocates collaborate with feminists, taking women’s needs and concerns into consideration. Women are often overlooked in data collection, and as a result, our needs are not met in city and transit planning, and our concerns about safety are shrugged off.

The sprawl of American suburbs made us a car-dependent country, but as they sprung up throughout the 1950s, they had the side effect of keeping women chained to the home. Currently, women are less likely to own a car than men, and no doubt this divide was even more pronounced 70 years ago, when the pressure on women to be mothers and homemakers was much stronger.

Though this isn’t as bad as it used to be, dense housing with amenities located nearby would still be liberating for women. It would allow her to walk to the bottom of her apartment, or just a couple of blocks away, to meet up with friends at a cafe. Running errands would consume less of her time, because she would not have to travel as far to get to a grocery store, or to drop her kids off at school.

As it stands, women still do more household errands than their male partners. While this obviously needs to be evened out, having errand destinations within a 15-minute walk or bike ride is more than just convenient. It allows for more free time that isn’t spent in traffic, and it gives us more opportunities for exercise.

As mentioned earlier, destinations that are not within walking or biking distance would be easily accessible via public transportation, whether in the form of buses, light rail and trams, or subways and metro systems.

Other types of infrastructure in these improved cities will also need to take women into consideration. We need spaces to breastfeed, but many of the solutions which currently exist are wholly inadequate. Some companies have developed “pods”, similar to portable toilets, for this purpose. I’ve seen a couple of them scattered around university campuses, but never anywhere else where it would matter, such as libraries or at parks.

Another absolute necessity for urban environments are public restrooms, but women’s needs have not been taken into account when constructing these. Aside from menstruation and childcare, women also have higher rates of urinary incontinence - an estimated 40% of women in the United Kingdom, and 62% in the United States, suffer from it.

In 2015, a woman in Amsterdam was fined for public urination, even though she had no available alternatives. At the time, there were 35 public restrooms for men in the city, and just three for women, only one of which was open 24/7. After the woman in question tried to fight the fine, a judge ruled against her, stating that women could just use a urinal in the men’s restrooms.

A lack of adequate facilities leads to holding it, which can cause UTIs, or forgoing water altogether, the latter of which is especially dangerous on warm days. I bring this particular example up because it’s not solely a matter of convenience - it’s also a matter of women’s health.

No city is complete without public transit. Women make up 55% of all trips taken via this mode of transportation, according to the American Public Transit Association. It’s a small majority, but given women have lower car ownership rates, it checks out. In spite of this, though, public transit networks are often planned and constructed with the average male commuter in mind, and women’s travel patterns are not considered.

A report published by the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe determined the following:

Men’s stereotypical role in almost all societies is the one of the income-earning breadwinner, who leaves the house for work in the morning and comes back in the evening. Women, however, usually perform triple roles as income earners, home-makers, and community managers. As a rule, they take shorter, more frequent and more dispersed trips during the day.

This is where biased transportation planning comes into play. As reported in Invisible Women by Caroline Criado Perez, many cities around the world use a radial pattern for their public transit networks. Bus routes and metro lines converge on a general “downtown” area, and then snake out and away towards the suburbs.

This pattern is easy to spot in American cities, which generally have fewer public transit lines than European cities. Light rail and metro lines in Los Angeles, Denver, Chicago, Washington, D.C., and Dallas, as well as many other cities, all radiate out from a general downtown area. Such configurations are designed around the travel patterns of men who commute from the suburbs to their downtown offices.

Even when not all offices are in a central downtown area, rail systems will often go out of their way to serve these as opposed to residential areas and errand locations. A notorious example is in San Jose, CA, where one of the light rail lines makes major deviations in order to bring commuters to Lockheed Martin, NASA’s Ames Research Center, and a host of office parks.

Commuter prioritization does not solely plague our railways. Rochester, MN’s bus network is made up of routes which join in their downtown area, making inter-neighborhood travel very inconvenient. However, it’s much easier to change bus routing than it is to do so with metros or light rail, because there is much less infrastructure involved.

Criado Perez references a study conducted in Chicago, which showed how these radial patterns add time on to public transit trips.

The study, which compared Uberpool (the car-sharing version of the popular taxi app) with public transport in Chicago, revealed that for trips downtown, the different in time between Uberpool and public transport was negligible - around six minutes on average. But for trips between neighbourhoods, i.e. the type of travel women are likely to be making for informal work or care-giving responsibilities, Uberpool took twenty-eight minutes to make a trip that took forty-seven minutes on public transport.

Even if someone is willing to sit through a longer ride to reach their destination, there are other factors which may make public transit inconvenient for them. Another sign of transit being designed around primarily male commuters are headways, or the amount of time between scheduled bus and train arrivals.

Many transit agencies design their schedules so that there are shorter headways during prime commute hours. For example, a bus or train which normally comes every 30 minutes would come every 15 minutes during rush hour. However, women who are traveling for caretaking duties or other errands would be taking public transit at all times of day, not just during rush hour.

Differing weekend schedules are yet another feature of commuter centricity. Since there are not as many people going to work on Saturdays and Sundays, buses and trains have less frequent headways. Some bus routes which connect suburban areas may not even run at all, making women’s inter-neighborhood travel much more difficult.

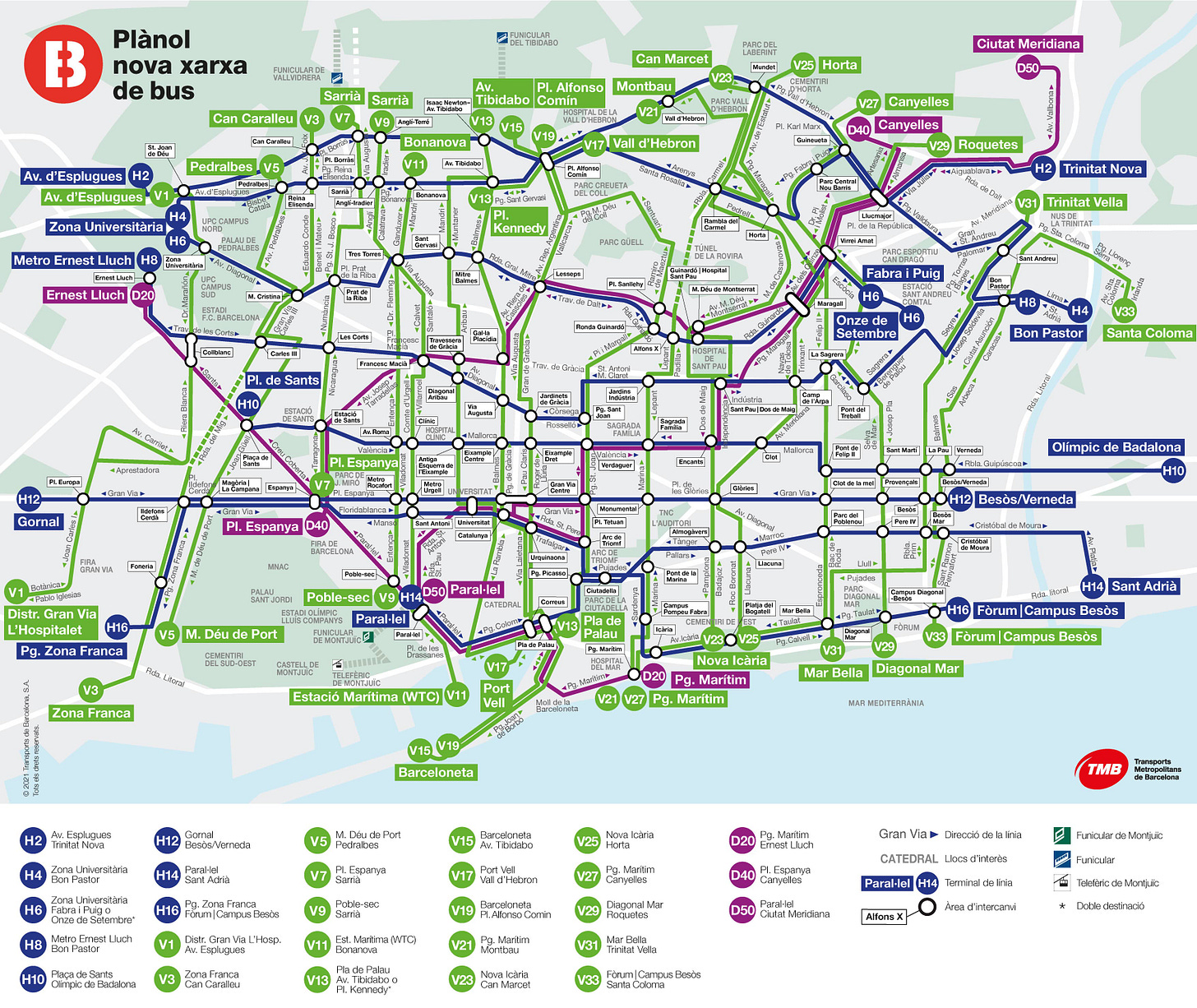

Barcelona’s solution to commuter prioritization was to design a new network of high-performance bus lines to complement their 69 other urban and neighborhood routes. Implemented throughout the 2010s, the network takes on a grid form made up of vertical and horizontally aligned routes, with a couple of extra diagonal routes.

These high-performance routes also have very frequent headways, with buses arriving every 5-8 minutes. This, and the general grid orientation, allows for more ease in making connections to other routes. Even if you arrive a minute too late, the next bus is not far away.

It’s not just women’s travel patterns which are unaccounted for in transit planning, though. Our concern for our safety influences how we use public transit, especially during rush hour and at night.

To be clear, many people are safety-conscious when using this form of transportation. Crime, when it occurs on public transit, is often sensationalized, leading to a perception that there is more of a risk associated with traveling via a bus or subway.

However, women are subject to sexual crimes and stalking, not just theft and assault. Men do not have to worry about another man feeling him up on a packed train, or getting off of a bus at his stop and following him home.

While misogyny and men’s sense of entitlement to our bodies is at the root of this problem, transit agencies should take steps to mitigate this behavior to the best of their ability. These mitigations are not permanent solutions, of course, but they’re not meant to be. They are measures which will help keep women safe while advancements are made in the deconstruction of patriarchy.

Take, for example, the Meri Seif buses in Papua New Guinea. After a study found that 90% of women had been sexually harassed while using public transit, these women-only buses were rolled out in Port Moresby and Lae during the 2010s. As of 2019, they served upwards of 600,000 passengers.

Other countries, such as Japan and India, apply this concept to their railways. Certain cars on metros and long-distance trains are designated as female-only. This works similar to women’s restrooms, in that men feel social pressure to stay out, because they have no good reason to be in there. Men who decide to ignore the signs and go in anyway are unceremoniously kicked out.

Bus drivers and train operators need to be trained to deal with incidences of sexual harassment and stalking. I don’t doubt that they are in many places, but without access to this training material myself, I have no way to gauge its depth or accuracy. I think that training on subjects such as these needs to be communicated to the public, so women can know exactly how an operator will be able to help them if their safety is threatened.

Urban and transportation issues vary from city to city, but the nature of women’s subjugation does not. Our needs and travel are not considered, and our safety is not prioritized. This is not an exhaustive article by any means, because there are so many things which need to be taken into account.

There are amazing people in the urbanist and transit advocacy spheres doing very important work. But all too often, the focus falls on fixing the problem according to men’s needs, not creating a more equitable solution for all.

This is not any one person’s fault. Maleness is so ingrained as the “default” that men’s travel patterns and needs in urban areas are just considered to be everyone’s needs. Most people don’t even realize that there is a problem with lack of female representation until they are made aware of it.

One of the best actions that urbanists and transit advocates can take to bring women’s needs into the discussion is to talk with us about our concerns. Somewhere out there, there is a woman who is waiting to be asked an important question:

What can we do for you?

Personal safety is a huge reason women drive rather than use transit, and as an environmentalist I find this very concerning. But who can blame women for choosing not to be harassed and intimidated in enclosed spaces, or when forced to stay in one place at night waiting for a train or bus.

I personally am not wild about women-only transit vehicles, because it leads men to believe that any women outside them are 'fair game' for harassment and assault. I'd like to think that making clear rules for behaviour and enforcing them is the most efficient and effective way to promote women's safety - IME men are good at following rules when they know breaking them has guaranteed consequences.

Here's a great idea from Brazil:

https://www.adsoftheworld.com/campaigns/guarded-bus-stop-case-study

Excellent and thorough post!